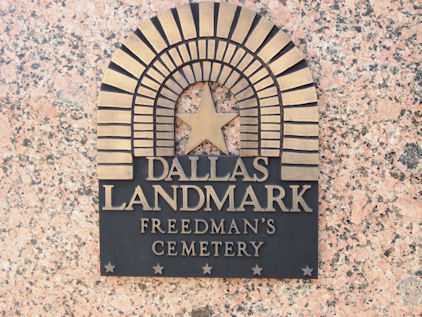

When last I left you, Gentle Reader, I was poised to describe the Freedman’s Memorial in Dallas, which is located at the former site of the old Freedman’s Cemetery. That cemetery was a local institution from 1869 until the 1930s, when it was largely wiped out by road construction. Its location (what’s left of it) is now a Dallas Landmark site.

One thing I have to say about this particular memorial is that it’s far more emotionally involving than the John F. Kennedy Memorial downtown, an attraction I’ve previously discussed on this site. The Kennedy Memorial is modernistic and, frankly, sterile; the Freedman’s Memorial is architecturally classic and emotionally wrenching. It does what a true memorial is supposed to do: it makes you feel the pain and sacrifice of the people it memorializes. And truly, given 200+ years of African slavery in America, and the century of Jim Crow discrimination that followed, there’s a great deal of pain to feel.

The Freedman’s Memorial is a mixture of park and sculpture garden. A wrought-iron fence surrounds most of the small park, which is planted in spreading pecan trees; during the summer it makes for a great space to walk around in, sit in the shade, or even have a picnic. Of course it was winter when I took this picture, so things are looking a little dreary.

The centerpiece of the memorial is the small contemplation area on the south side of the park; this is where the main entrance is located. The entry arch and adjoining walls, along with the facing of the benches and planting areas, are constructed of polished red granite — probably that famous central Texas type known as Texas Red, which is mined near Fredericksburg and Enchanted Rock. Bronze plaques on the inside walls of the Memorial display the text of short poems written specifically for the memorial. But while all this is beautiful, the real draw is the incredible statues crafted by artist David Newton. Not only are there five larger-than-life statues in the park, mostly associated with the entry arch, there are a dozen smaller African totem-type statues inset in niches at the top of the arch, six on either side. All 17 of the statues appear to be constructed of dark bronze.

On the east side of the entryway, as you go in, are two statues on pedestals, both life-sized or better. The one on the left is of a heroically-muscled African warrior, complete with wicked-looking sword; the one on the right is a griot, or prophetess. These two represent the proud African culture of the ancestors of the Freedmen this site memorializes. Both are visible in the above photo. Here’s a closer view of the warrior, on the southeast face of the arch.

On the western face of the entry are two works, set into the arch itself, that I suppose you would call friezes. Both are absolutely stunning, and represent the African-American experience of slavery.

The one to the south shows a black man straining at his chains; the one to the north is a woman, similarly bound, in an attitude of utter despair. This one will break your heart. The level of detail is amazing, right down to the corn-rows in her hair, and the chains themselves, which really are chains.

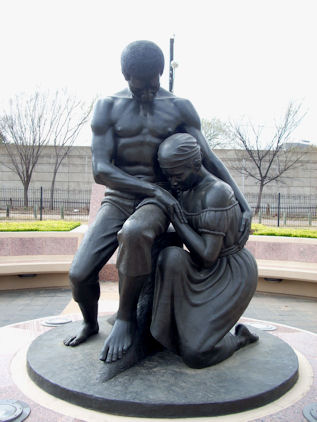

The final David Newton statue is in the center of the contemplation area, on a dais in the middle of a circular walkway. It shows a man sitting on a stump, with whip marks visible on his back; beside him crouches a woman, embracing him. They’re both in 19th century clothing, indicating that they represent the freed blacks (freedmen, as they were called) of the post-Civil War era. Their attitude is more sorrowful than hopeful, considering what they’ve been through and how they’ll be treated in the future; but at least they can call themselves free. From this point, many of their descendants managed to claw their way up from destitution, despite the ingrained discrimination they had to face in both North and South, to make something of themselves.

This is powerful stuff, folks. Mr. Newton is an incredible artist. You don’t have to be African-American to feel the impact (I know because I’m not). The City of Dallas has done itself proud here, in stark contrast to the moribund Kennedy Memorial in the West End. Quite probably this was due to the fact that, rather than wanting to sweep this bit of history under the rug, local civic groups (especially the Africa-American ones) struggled long and hard to bring it to the forefront. Slavery was awful, yes, but there’s no ignoring it — or there shouldn’t be, if only (to paraphrase George Santayana) so we’re not doomed to <> repeat something like this. And don’t fool yourself into thinking it couldn’t happen again…we seem to be losing our civil rights at a fairly rapid rate these days.

The Freedman’s Memorial may have been a long time coming, but it was worth the wait. You’ll find it just south of the intersection of Central Expressway and Lemmon Avenue in East Dallas, immediately east of the historic Temple Emanuel Cemetery, which is also something to see if you like that kind of thing.

What hours does this museum operate??

Hi Elaine,

It’s more of an open-air park than a museum, and as far as I know it’s open all the time.

Floyd

Thanks for taking the time to share this. It’s incredible.